Photo by Andrew Reding. Western tent caterpillars. 2014. CC. https://flic.kr/p/nwEuEP

(This post was inspired by my father, who saw tent caterpillars in July and told me I should write a blog post about them. Merry Christmas Dad!)

Me: What a lovely June day. The bees are buzzing, the flowers are blooming, the caterpillars are swarming. Wait, why are caterpillars swarming my Aspen tree? Get off of there!

Western Tent Caterpillars: Make me. I’m a native species, and I’m not doing anything wrong.

Me: You’re a gross creepy crawly mass of caterpillars, that’s what’s wrong.

W: Well we can’t all be hairless apes like you.

Me: And look at what you’re doing to this poor tree! You’ve eaten half of its leaves. How is it supposed to survive?

W: I wouldn’t worry about it. Trees are pretty good at bouncing back. Our population explosion will be over soon anyways. Maybe another four years or so.

Me: Four years? You mean I’ll have to stare at hundreds of wriggling caterpillars for another four years?

W: That’s what it looks like, yes. These explosions happen every decade or so.

Me: That is not very comforting. Why does your population explode anyway?

W: What can I say, sometimes the world needs more caterpillars. The cycles depend on weather, predators, pests and other factors. You guys haven’t cared to study us very much, so I’m not giving anything away.

Me: Will my poor aspen tree end up dead as a result of your munching?

W: It’s a pretty healthy specimen, so probably not. Healthy trees don’t usually die from infestation, it just make them weaker and more vulnerable to pests and drought.

Me: That’s not very comforting.

W: If it’s any consolation, the tree’s fighting back. It can make its leaves less nutritious next year, so fewer of us will survive. Anyways, getting rid of some leaves in the canopy actually helps the environment.

Me: Oh really? How’s that?

W: Fewer leaves means more light and rain reach the forest floor, giving saplings down there a chance to grow. I’ll also have you know that caterpillar poop is an awesome fertilizer.

Me: Eww, I didn’t really need to know that. How did you all get on my tree in the first place?

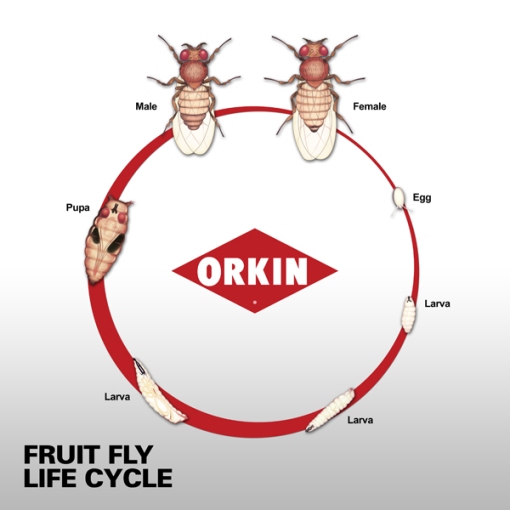

W: Mom put us here. Last August she laid a huge cluster of 300 eggs around a twig and covered us in this foam that hardened to look like grey Styrofoam. The finished clutch was as big as she was!

Me: Sounds pretty impressive.

W: It was! We started developing in our eggs, then took a long nap over the winter.

Me: What happened when you hatched? Why did you stick together?

W: We hatched just as the leaves started appearing in April. All of the larvae from that eggs sack decided to hang out because we are social butterflies. Okay, social moths.

Me: Why do they call you tent caterpillars?

W: Life as a soft and squishy caterpillar is not easy. Birds and rodents want to eat you, and parasitic wasps want to lay eggs in your insides. It’s very unpleasant. To avoid this, the colony builds a giant silken tent to hide under. If we aren’t feeding we’re in the tent. It’s shelter from the weather, protection from predators and a place to molt and grow.

Me: I’ve seen you stick your bodies out of the tent and twitch them. Is that a caterpillar dance party?

W: Nope, it’s a defense mechanism. We do it whenever a possible predator passes by. Hopefully they’re so confused they just keep walking and don’t try to eat us.

M: You said you turn into a moth, right? How long before that happens?

W: About 4-6 weeks after we hatch, everyone in the colony separates and finds their own spot to make a silken cocoon. We’ll pupate on anything from aspen leaves to house siding to lawn mowers.

M: I can’t wait.

W: Don’t worry, 10 days later we’ll emerge as beautiful light brown moths. Those moths flitting around your porch light are probably us. We usually mate within 24 hours of emerging.

M: Whoa, you don’t waste any time, do you?

W: Nope. Every female lays one egg clutch, and our whole life cycle takes about a year.

M: Yeah, but for most of it you’re stuck in an egg.

W: Touché.

M: So does this mean that my aspen tree will be infested by your children next year?

W: Probably. We are Canada’s national champion of eating leaves off aspen trees, after all.

M: I guess I’d better get used to you then.

W: Yep. You could spray pesticides on the tree, but that would kill the beneficial bugs too. It’s best just to let our predators or the weather finish us off.

M: Okay, I’ll leave you be… this time.

W: We appreciate it!

References

Click to access Tent-CaterpillarsDRAFT041113.pdf

http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/forests/fire-insects-disturbances/top-insects/13379

http://esrd.alberta.ca/lands-forests/forest-health/forest-pests/common-tree-insects-diseases/forest-tent-caterpillar.aspx

http://www.cityofgp.com/index.aspx?page=915

http://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/tent-caterpillar-outbreaks-plague-canadian-communities-1.1881540

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/tent-caterpillars-defoliate-peace-country-1.1198924

http://www.countygp.ab.ca/EN/main/departments/agriculture/pest-disease-control/forest-tent-caterpillars.html

http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/healthy-living-vie-saine/environment-environnement/pesticides/tent-livreeamerique-eng.php