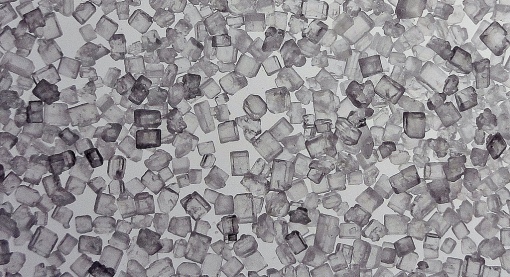

Photo par ruurmo. Aguacates para todos. CC. https://flic.kr/p/fN5wX (pile)

(Read the English version of this post)

J’apprécie la chair succulente d’un avocat, mais il faut admettre qu’il est un fruit bizarre.

Voici pourquoi.

On ne connait pas son ancêtre sauvage

Les Mexicains cultivaient les avocats bien avant l’histoire écrite, alors on en sait peu sur ses origines. Les Incas l’ont découvert en 1450 après avoir envahi une communauté qui les cultivait.

Les explorateurs européens avaient aimé la texture beurrée de l’avocat et l’ont vite transporté dans toutes leurs colonies avec un bon climat pour le cultiver, y compris les Antilles, la Californie et la Floride. Aujourd’hui, le Mexique est le plus grand exportateur des avocats, suivi de la Californie, l’Israël et l’Afrique du Sud.

Une poire alligator dans ton sandwich?

Photo par torbakhopper HE DEAD. CC. https://flic.kr/p/fpwPr

Au début du 20e siècle, l’avocat avait au moins 40 noms différents, comprenant aguacate (le nom donné par les Incas), avigato, albecatta, avocatt, le beurre aux légumes, la poire au beurre, beurre de l’aspirant et mon préféré, la poire alligator! Avec tout ce choix, comment est-ce qu’on s’est décidé sur l’avocat? C’était aux États-Unis, où la Californie les appelait aguacate et la Floride les appelait les poires alligators. Le Département de l’Agriculture a décidé que le nom poire alligator était désagréable, et a suggéré le nom avocat à sa place. Au fil du temps le nom avocat est devenu la norme pour l’industrie. Sinon, on mettrait tous des poires d’alligators sur nos tacos!

Une stratégie de reproduction unique au monde

Photo par Cayobo. Avocado Flowers. CC. https://flic.kr/p/zbPB

Comme beaucoup de plantes, chaque fleur d’un arbre avocat ont des parties mâles et femelles. Bizarrement, ces parties ne sont pas actives en même temps. Les parties femelles fonctionnent deux ou trois heures pendant la première journée. La journée suivante, c’est le tour des parties mâles.

Beaucoup d’arbres utilisent la stratégie d’auto-fécondation, mais c’est impossible chez l’avocat. Si un arbre n’est pas à côté d’un autre qui a des fleurs complémentaires, il ne serait jamais pollinisé. Pour cette raison, les producteurs d’avocats doivent s’assurer qu’ils ont des arbres complémentaires dans leur ferme. Heureusement, il y a plus de mille variétés d’avocat, alors ce n’est pas difficile.

Une baie verte

Photo par Jaanus Silla. Avocado. CC. https://flic.kr/p/68eBn2

Un avocat est une baie, selon la définition botanique. Comme les bluets, les tomates et la citrouille, toutes les baies provenant d’un seul ovaire. Les fraises et les framboises ne sont pas des baies botaniques, mais ceci est un sujet d’un autre article.

Un arbre impressionnant

Avocado tree in bloom. Photo by Cayobo. Avocado Tree In Bloom. CC. https://flic.kr/p/mg7qZw

Si vous plantiez une graine d’avocat, vous attendriez les fruits cinq ans ou plus. Mais ça vaut la peine d’attendre. Un arbre âgé de cinq à sept ans peut produire 200 à 300 fruits par année! Les arbres sont productifs toutes leur vie. Il y a même des arbres de 400 ans au Mexique qui produisissent toujours des fruits. Mais au lieu de planter un arbre, ça va plus vite de chercher un avocat à l’épicerie et d’attendre les cinq à 10 jours qu’il prend à murir!

Une économie précaire

Les arbres d’avocat produisent des fruits d’une manière cyclique— des années extrêmement productives sont suivies des années moins productives. Ces cycles de-haut-et-de-bas peuvent être difficiles pour les fermiers, parce que la demande pour le fruit reste constante. Cette industrie perd des millions de dollars dans les années où il y a moins d’avocats.

Les chercheurs essayent de trouver une façon de régulariser la production, mais ils n’ont rien trouvé jusqu’à cette date. Les producteurs en Californie ont trouvé une solution au surplus dans les années 1960s – geler les avocats avec de l’azote liquide. Les restaurants peuvent les décongeler au besoin.

Sucré ou salé?

Photo par Kimberly Vardeman. Avocado Ice. CC. https://flic.kr/p/9VsoZE

La façon dont on mange un avocat dépend du pays et de culture. En Amérique du Nord ils sont additionnés aux salades et aux sandwichs. Au Brésil ils sont servis avec de la crème glacée ou dans un milk-shake. Á Java, ils sont mélangés avec du café et du sucre. Mais un avocat est toujours mangé cru. Pourquoi? Ils contiennent des tanins, un produit chimique qui donne un gout amer s’ils sont cuits.

Pas juste pour manger

Photo par Erin Costa. Pink Strawberry Soap_KRISTIE 2. CC. https://flic.kr/p/bmC7W4

Un tiers des avocats produits au Brésil est transformé en l’huile. On nourrit les animaux avec ce qui reste du fruit après l’extraction.

On peut garder l’huile d’avocat à 4 degrés Celsius pendant 12 ans. À cause de cette stabilité, l’huile est idéale pour faire des cosmétiques et des savons.

Les références

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/General/ThreeGroups.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/General/FruitBerry.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/General/Answers.html#anchor738397

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/General/HistoryName.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/General/Introduction.html

https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/avocado_ars.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/AvocadoVarieties/Hass_History.html

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/45866/avocado

https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/avocado_ars.html

https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/avocado_ars.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/Flowering/Figure3.html

http://ucavo.ucr.edu/Flowering/FloweringBasics.html