It wasn’t until I saw fields of sunflowers in the south of France that I ever thought of these yellow flowers as a crop. From mayonnaise to snack food, there’s more to these blossoms than meets the eye.

North American origins

Sunflowers, like blueberries and cranberries, are one of the few crops native to North America. The wild ancestors of most of the world’s food plants, like wheat, corn and potatoes came from the Middle East, Asia or South or Central America.

Wild sunflowers, which were much smaller than those grown commercially today, were first domesticated around 5,000 years ago by the peoples of the south-western United States. The high-protein seeds were valued by some indigenous peoples who used ground seed meal to make bread. The flower hitched a ride across the continent, and was seen by the first European explorers in locations ranging from southern Canada to Mexico.

An oil popularized by Russia

Europeans were not especially excited by the sunflower, and it was probably first brought to Europe by the Spanish as a mere curiosity. However, in the 18th century, Russia and the Ukraine adopted the sunflower for its high-quality, sweet oil. At the time sunflower seeds were around 28% oil, but Russian breeding bumped that up to nearly 50%.

These oily sunflower hybrids gained popularity in the U.S. after WWII. In 1986, sunflowers were the third largest source of vegetable oil world-wide after soybean and palm oil. However, these days they only make up only 9% of the world’s veggie oil market. The leading producers of sunflower seeds are Argentina, Russia, Ukraine, France, the U.S. and China.

Sunflower oil is used in salads, cooking oil, margarine and mayonnaise. It is also added to drying oils for paints and varnishes, as well as being used in soaps, cosmetics and bio fuel. Once the oil is pressed out of the seeds, the remaining high-protein meal is used to feed chickens and livestock. This meal can also be a flour substitute in bread and cakes.

Snack time: A mouthful of achenes

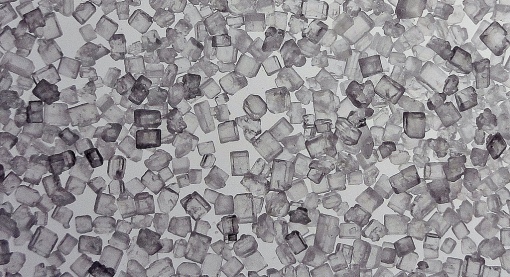

Photo by Mark S. “Sunflower Seeds”. CC. https://flic.kr/p/bbKcST

The sunflower ‘seeds’ sold as snack food are actually fruit. In botany-speak they’re called achenes, a fruit with a hard outer coating. The real seed is the grey ‘meat’ in the centre.

Sunflowers grown for their achenes are different varieties from oil seed sunflowers, which have smaller black seeds. ‘Confectionery’ achenes have thicker hulls and lower oil content, not to mention stylish black and white stripes. They are served salted and roasted, or hulled for use in baking. With 20% protein, the achenes and seeds marketed as healthy snacks, and meat substitutes.

Sun worshipers

Many people think that sunflower heads always face the sun (called heliotrophism) but that simply isn’t true. The early flower buds spiral around until they face east like living compasses, but they stop once they bloom. The leaves also follow the sun, which makes sense: they are the ones that need the light for photosynthesis, not the flower.

Manitoba: Canada’s sunflower capital

Photo by William Ismael. “Sunflower Seeds.” CC. https://flic.kr/p/9rqvXr

Canada has grown sunflowers commercially since the 1940s. Over 90% are grown in Manitoba, where 250 million pounds of sunflower seeds are harvested annually. The rest are grown in Saskatchewan.

70% of all Canadian sunflowers are of the confectionery variety, and primarily serve Canadian markets. Some are exported to the U.S., The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and China, which are large consumers of hulled sunflower seeds.

Canada also grows oil seed sunflowers, but because there is no large-scale sunflower crushing facility in Manitoba, the achenes are sent to the U.S. for processing.

Floret power

Despite popular belief, sunflower heads are not one flower, but a composite of many tiny flowers called florets. One sunflower head can contain up of 1,000 to 2,000 florets. The sterile petal-like ray florets draw in the pollinators, but real pollination happens with the black and brown disk florets in the centre. These fertile disk florets are arranged in a spiral, and shed pollen beginning at the edges and moving to the centre. Disk florets very sensitive to frost; any temperature below 0 degrees Celsius will cause rings of sterile florets.

Now there’s something to think about the next time you enjoy a carrot muffin topped with sunflower seeds.

References

Click to access vegetableoilstudyfinaljune18.pdf

http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/plants-fungi/helianthus-annuus-sunflower

http://www.britannica.com/plant/sunflower-plant

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sunflower/

http://www.canadasunflower.com/production/sunflower-agronomy/

http://www.gov.mb.ca/trade/globaltrade/agrifood/commodity/sunflowers.html

http://www.agr.gc.ca/eng/industry-markets-and-trade/statistics-and-market-information/by-product-sector/crops/pulses-and-special-crops-canadian-industry/sunflower-seed/?id=1174599801414

https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/afcm/sunflower.html